The Genesis of the “Hong Kong Diaries”

17 journalists, eight Hong Kong residents, two months, and one terabyte of data: the “Hong Kong Diaries” is a mega-project. In this text we want to explain how it came about and which aspects were important in order to be able to weave everything together in the end.

Being Close

Hong Kong – there are many films and even more texts about the city. But we wanted to be closer. Very close to the people in Hong Kong who fight for democracy every day. But how do you accomplish that when you can’t send reporters?

It sounds unspectacular, but the answer is simple: writing emails. We contacted more than 50 people in Hong Kong. Politicians and lawyers, students, artists, athletes and salespeople. The goal: to find Hongkongers willing to document their lives for two weeks. Answering questions every day and giving us an insight into their fight for democracy.

Thinking Like the Secret Service

Before the first email was sent, we firstly discussed security. It quickly became clear that all communication, both within the team and to Hong Kong, had to remain encrypted. This ensured the protection of all Hong Kong residents with whom we came in contact. That was the highest priority, because in the worst case, communication with us could be interpreted as cooperation with foreign powers – and send our interlocutors to prison.

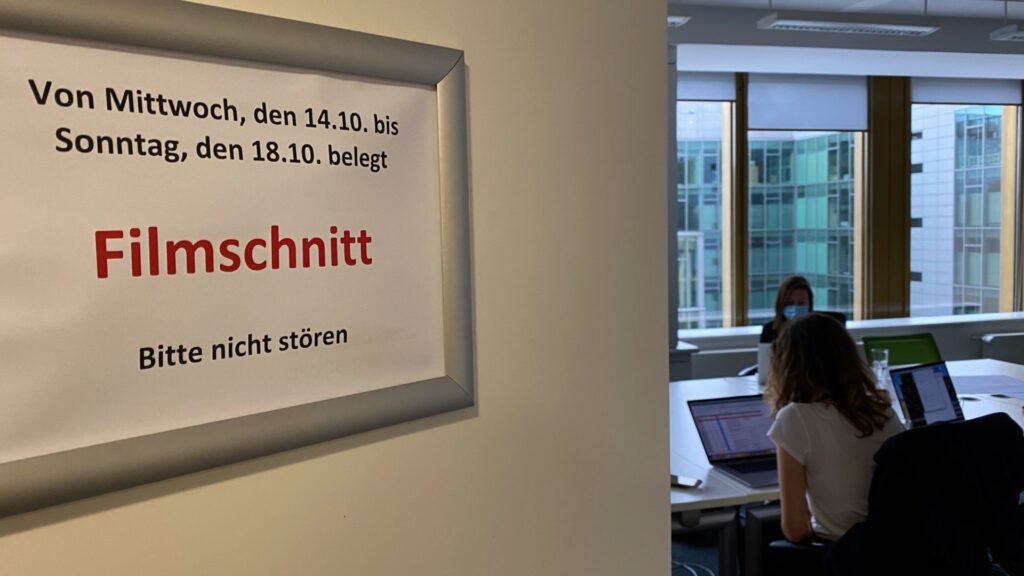

Sensitive data and details were not allowed to be exchanged via email, WhatsApp, or Slack. Every video conference, every phone call, every file – everything that makes one of the Hong Kong residents identifiable – had to be kept secret. But that’s not all: every file we received from Hong Kong was allowed to be saved only locally on encrypted hard drives. No servers, no clouds. Sometimes we did not even say our correspondents’ real names out loud in our team. Instead we gave them cover names. Some of the protagonists were renamed several times over the course of the weeks.

Eight People for Hong Kong

A project like the “Hong Kong Diaries” requires long and intensive research. This also includes a background check. Before we made someone part of the project, the following questions were unavoidable: Does this person really exist? Or are we falling for an account by the Chinese authorities on an undercover mission? Are there gaps in the resume of the requested person? If so, can this be explained or could military or intelligence training have taken place during this time?

After much back and forth, eight Hong Kong residents were finally ready to take part in our project. Five of them even took a big risk and showed themselves with their faces and real names from the start. Three of them remained anonymous. They were given pseudonyms and were always masked on videos. But that wasn’t all. Our security team had to constantly examine the material made available for publication and notify the protagonists of any security gaps. For example, in one case, the reflection in sunglasses could have led to finding out where the photo or video was taken. Even such little things could have exposed a person’s identity.

Paying attention to safety also meant not letting any external reporters or cameramen accompany the protagonists in Hong Kong. So we had no choice but to let them film themselves and provide them with the necessary technology. They all got the same equipment: an iPhone 11, an external microphone, a small tripod, and a light. One of our protagonists got a 360-degree camera. A new iPhone 11 was very important, because it enabled us to ensure that the device was “clean”.

Two Weeks of Intensive Contact

From the 28th of September onward, eight Hong Kong residents took us into their lives for two weeks. For this, each protagonist got a personal supervisor from our team. The initial concern that they might send too little material quickly turned out to be a fallacy. We received a huge amount of data already on the first day. And every day we kept on asking questions, which were answered via chat, video, or voice message.

To avoid a data chaos, the material that reached us from Hong Kong had to be carefully viewed, tagged, and then sorted and saved on encrypted hard drives. What can you see in the video? What is said? When and where was it recorded? How was the weather? This was the only way we could keep track of things and find suitable material for the documentary and multimedia stories during post-production.

Eight Unique Stories

Our goal was to tell what the life of eight Hongkongers was like at a time when communist China is increasingly restricting democratic freedoms. And because the protagonists reflect this problem in very different ways, we decided to tell their stories with individual multimedia diaries. Their personal texts, photos, videos, chat excerpts, and voice messages now bring you closer to the reality of eight democratically thinking Hongkongers. A direct and almost unfiltered impression, supplemented by classifications from our side. These multimedia stories go into detail where the 20-minute documentary reaches its limits. The documentary therefore shows only four of the eight characters, whose fight for freedom could not be more different.